House of Review was JATL’s third social justice forum for 2015 and it examined whether Queensland should restore its upper house. Chaired by Professor Nicholas Aroney (TC Beirne School of Law), students had the unique opportunity to witness a lively debate on the topic between two masters of the art, with Mr Anthony Morris QC (barrister) in the affirmative and Ms Rachel Nolan (former Queensland Government Minister) in the negative.

Rose: “Good evening everybody and welcome to JATL’s third social justice forum for 2015. I’d like to say thank you to our speakers, and I’d like to recognise the traditional owners of this land, the Turrbal and Jagera Peoples. Tonight’s forum will look at whether Queensland should restore its upper house in the context of it being the only unicameral state parliament in Australia. We are happy to welcome Professor Nicholas Aroney from the TC Beirne School of Law, and our speakers Mr Anthony Morris QC and Ms Rachel Nolan, a former Queensland Government Minister. Thank you very much for your time and wisdom. Nicholas Aroney is a future fellow at the centre for public international and comparative law. The purpose of his research in the fellowship is to identify the principles and values that should underlie the Australian governmental system. He is very well placed to act as our chair on this topic. Professor Aroney has published widely on the topics of constitutional law and legal theory and has held several positions at Australian and foreign universities. We are very fortunate to have him currently at UQ. Without any further ado please welcome Professor Aroney.”

Nicholas Aroney: “Thank you very much for such a kind introduction and it is nice to talk to some of the students that I never get to know. The good news is I’m coming back to teaching next year. It’s my pleasure to introduce the debate this evening. My role is to provide you with some background information to contextualize the debate so the speakers can focus on their arguments.

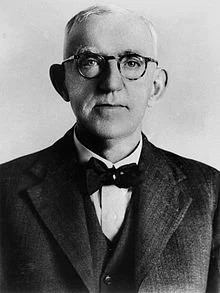

Professor Nicholas Aroney

Queensland is the only state without a second chamber. All the other states have a legislative assembly or legislative council, and they are both elected in two different ways so their composition tends to be a little different and so they perform functions somewhat differently in those states. In Queensland there is only one house. What that means is that whichever party secures the most votes holds not only the position to be in government but they are also in the position to legislate. Executive and legislative power is concentrated in the same political hands. The Queensland parliament does have a committee system which does moderate that to some degree, particularly to the extent that those committees provide feedback and review of legislative proposals or review matters of political importance. Particularly when those committees are composed of backbenchers who are frank and fearless or leaders of the opposition as well.

A lot of the debate is about understanding our political system, like our parliament and how it operates, and other institutions like the CCC that looks into crime and corruption matters. Upper houses can be constructed in many different ways. In New South Wales there are forty-two members of the upper house who are elected on a rotational basis, twenty-one members at a time on a proportional system. The quota to get elected is low in New South Wales and relatively small parties and independents are able to be elected. This provides for a variety of representatives in the New South Wales upper house. The South Australian upper house elects eleven at a time, so the quota is a bit higher. In Victoria and Western Australia and in some cases Tasmania (Tasmania is upside down, as the lower house has proportional elections) the number of representatives is based off five or six regions, not the state as a whole. These design features of upper houses have an impact on their capacity to function within the bicameral system.

So why is Queensland different from the other systems? When Queensland became a state in 1859 it did have a second chamber. When it split from New South Wales the imperial statute that related the order in council that established Queensland required there to be a parliament as similar as possible to that in New South Wales. At that time, whilst the lower house was elected the upper house was nominated by the governor on the advice of the reigning Premier, so it wasn’t an elected body. Around 1915 till 1925 the first Labor government came into power under T. J. Ryan and Ted Theodore, and they tried to remove the upper house. The upper house didn’t want to vote itself out of existence. At some point the government made use of the referendum procedure that was established in earlier legislation so it went to a referendum. It is controversial how the referendum was presented and if the people had a decent chance to think about it but they voted against the abolition of the house. Then the Theodore government appointed additional members to the upper house and over several appointments the Labor government was able to get through the statute to abolish the upper house. So the members of the upper house effectively voted themselves out of existence and we haven’t had an upper house since.

The one other thing to appreciate, several years later in 1934 another statute was passed which entrenched the absence of an upper house. A lack of an upper house is entrenched and it can only be revived by a referendum. In all of the other states, excluding Tasmania, upper houses can only be removed by a referendum, so referenda are entrenching mechanisms in all of those five states, but in a reverse way in Queensland. Those entrenching provisions were not introduced by referendum so there’s a deeper question whether it is legitimate for a referendum procedure to be imposed when that imposition wasn’t approved by referendum itself. So there are remaining questions about that and case law on the issue, the High Court hasn’t said there is a problem with that but maybe there is a question of legitimacy. So they are the essential things I wanted to convey to you by way of the debate.

It is now my pleasure to introduce our two speakers for tonight. For the affirmative, that the upper house should be reintroduced is Mr. Tony Morris QC. He is a barrister here in Queensland, his principle areas of law are commercial law and equity, and he has come before the High Court in several matters. He took silk at the age of thirty-two and his appointment as QC was the youngest in Queensland’s history. The subject of youth is an interesting point about both our speakers. He’s a member of various boards and an established author, having written at least once or twice on the topic of an upper house in Queensland. He was also the commissioner of the Bundaberg Hospital Inquiry.

Our second speaker is Ms Rachel Noland who was a minister in the Bligh Labor government. When she was first elected as a member for Ipswich in 2001 she was the youngest woman to be elected to the Queensland Parliament. So these are two high achievers that we have to listen to today. She now writes for the monthly and is an adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Queensland.”

Tony Morris QC: “Thank you Professor Aroney and thank you all for your significant contribution to the public discussion of this issue, which I think needs to be discussed more. I will begin with three confessions, the first is how delighted I am to be in this building. It was derelict when I was a student thirty-five years ago and I’m delighted to say the blistering paint in the stairwell still hasn’t been touched up. The second confession is I’m going to cheat a bit, because the topic is should Queensland restore its upper house, and this is because no one would seriously suggest we restore the type of council we had prior to 1923 which had people appointed for life so it was like the Australian equivalent of the House of Lords. The third confession is rather like how I go to court everyday with well-prepared notes and get on my feet and abandon it entirely. I’m going to approach things in a different way from what I originally intended.

Tony Morris QC

Given the informal nature in which this is being presented, I’d like to begin with a pop quiz to demonstrate how little any of us know about our state’s political history. Rachel has a significant advantage over us, as someone with a distinguished political career, but Rachel may also throw in an answer if she so wishes.

Question One: Who was the first Queensland Premier who attempted to rig the outcome of an upcoming election by changing the electoral laws in a way so as to benefit his own party? Any thoughts? Campbell Newman? Joh Bjelke-Petersen? Actually you have to go back to 1915 when Digby Denham was worried that Labor was more organized than his own party. He was worried the Labor Party, which was largely run by shop stewards at that time, was very good at getting people to the polling booths to vote. So his government was the first in the British Empire to implement compulsory voting to ensure that Labor’s advantage did not lead to his determent. It didn’t work and he lost the election. For those who see a similarity with Campbell Newman, the similarities go even further, Digby Denham was the first Queensland Premier to lose his seat at a general election. Newman matched this singular achievement a century later. But this phenomenon is not unique to the non-Labor side of politics. In 1942 William Forgan Smith noticed Labor was doing badly in three-cornered contests, where you had a Labor candidate against a Liberal candidate and a Country Party candidate. To get around this problem, Forgan Smith was the first leader, anywhere to my knowledge and I suspect the last, to abolish preferential voting and go back to the first past the post system. This was to ensure the non-Labor forces didn’t benefit from three-cornered elections. That’s Question One.

Question Two: Which Queensland Premier was responsible for the most obscene gerrymander in Australian history? We all think Bjelke-Petersen. We think that because our knowledge of Australian history is based on two things; our own memories and what we’ve been taught by educators and journalists. All of those people are of my generation or younger, they are post baby-boomers and they can’t remember a time before Bjelke-Petersen. It has become the received wisdom that bad government began with Bjelke-Petersen, had a resurrection under Campbell Newman, but otherwise didn’t exist. Absolute nonsense. I’m not here to defend what Bjelke-Petersen did, his gerrymander was an outrage, at the height of it the largest seat was Pine Rivers at 16,700 voters and the smallest was Gregory at around 6000, a margin of about two and a half. If you think that’s an outrage think about what Ned Hanlon’s government did in 1949, when the seat with the most votes was Mt Gravatt at 26,000 and the smallest was Charters Towers with 4000 voters, six times smaller than Mt Gravatt. Under the Hanlon system for his government to win a seat they needed 7000 votes, coincidently it was the same under the Bjelke-Petersen’s government. They also needed 7000 votes to win a seat, but there were of course many more voters when Bjelke-Petersen came along. For Labor to win a seat under Bjelke-Petersen, they needed 12,800 votes. Under the Ned Hanlon government the Country Party needed about 9900 votes, the Liberals needed 23,000 votes to win a seat. If you’re looking at gerrymanders that’s a great one.

Question Three: When the gerrymander was brought in, in 1949, which future Premier of Queensland decried it saying that the minority will rule the majority? He said that the government of the day was proclaiming that whether you like it or not we will be the government. Who would have said that? Vince Gair, Frank Nicklin, Jack Pizzey, Gordon Chalk, Mike Ahern, Wayne Goss or Peter Beattie? No it was the newly elected member for Nanango, Johannes Bjelke-Petersen.

Question Four: Who was the first Queensland Premier to be the subject of corruption findings at a commission of inquiry. Fitzgerald's was not the first. In 1929 we had a royal inquiry, it concerned the purchasing of mining properties by the state government. The corruption revealed was of a nature and scale that rivaled anything uncovered by the Fitzgerald Inquiry. The properties were purchased at vastly more than their actual value and it only emerged at the inquiry that two Labor Premiers each secretly held a 20% interest in the company that sold the land, those being Ted Theodore and William McCormack.

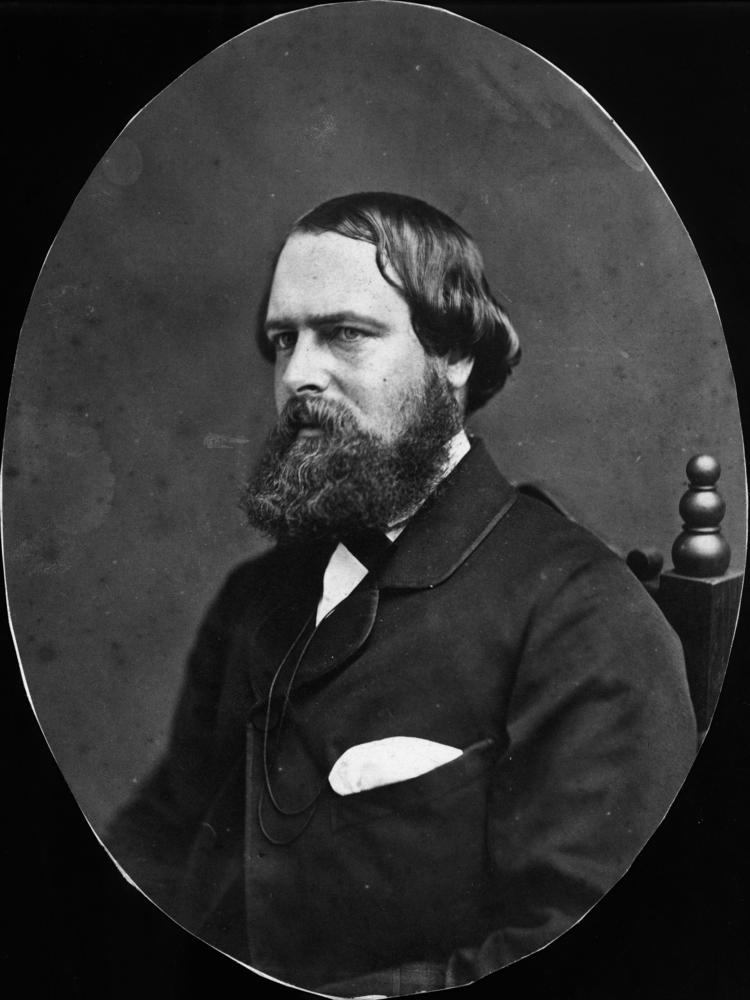

William Forgan Smith

Question Five: Which Queensland Premier was responsible for the legislation that was famously used to create a state of emergency, so as to suppress anti-apartheid demonstrations at a Springboks rugby match in 1971? We all know it was Bjelke-Petersen invoking the legislation, however it was based on the State Transport Act passed by the Labor government under William Forgan Smith in 1938. Peter Beattie is said to have admired Forgan Smith and I’m not sure why. Wikipedia begins its article on Forgan Smith with the observation that his populism, firm leadership, defence of states’ rights and interest in state development make him something of an archetypal Queensland Premier and it goes on to note that Forgan Smith was also a typical Queensland Premier in that he was criticized for being authoritarian and dictatorial, that he used his strong and forceful personality to dominate cabinet and his government passed a number of pieces of controversial legislation. I can’t resist but tell you one Forgan Smith anecdote. In the late 1930’s Queensland was doing badly, it hadn’t recovered from the Great Depression of 1929, and Forgan Smith went on a global fact-finding mission to see how other parts of the world were dealing with the aftermath of the Great Depression. What he liked best was what he saw in Germany. The first thing he did upon his return in 1938 was to create the office of Coordinator-General, a position to this day that is unique to Queensland. The Coordinator-General has the responsibility over the development of what are described as ‘state significant projects’, large-scale infrastructure projects both public and private. Forgan Smith saw this as achieving the level of efficiency he had witnessed first hand under the Third Reich.

Question Six: Which Queensland Premier was most active in defending states’ rights against perceived federal incursions? I won’t go into details, but T.J. Ryan wins hands down over Bjelke-Petersen or anyone else.

And finally who was the first openly gay Premier of Queensland? It’s a trick question because we’ve never had an openly gay Premier, but the first Premier of Queensland was a man called Sir Robert Herbert. He was the grandson of the Earl of Carnarvon, a distinguished scholar educated in Eton and Oxford. He had been private secretary to William Ewart Gladstone. At Oxford he met his long-term companion John Bramston, they shared rooms together at Oxford, when they went to London they shared rooms again, when Herbert came out to Queensland, originally as private secretary to the first Governor (Governor Bowan) Bramston decided to come with him. Herbert as Premier in the first state government appointed Bramston as Governor General. They shared a house on the future site of the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital and they named that house after a combination of their surnames, Herbert and Bramston, which they called Herston, hence the suburb of that name. Herbert went back to the UK and was appointed Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, a job he held for 21 years. Bramston was appointed Assistant Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies and held that job for 20 years. Upon his retirement from the public service in 1892 Herbert became chancellor of the Order of St Michael and St George and Bramston became registrar of the Order of St Michael and St George. Bramston eventually married but Herbert never did. I’ll invite you to draw your own inferences from that cautionary tale.

Why did I tell you all these random facts from Queensland’s political history? Well Karl Marx observed that history repeats itself twice, the first time is tragedy, the second is farce. Those who only know of Bjelke-Peterson and Campbell Newman think that’s just one side of politics, but that simply isn’t true. What we can learn from history is that the excesses of Forgan Smith, Hanlon and Gair governments, Labor governments, were repeated by Bjelke-Peterson as abject tragedy and then by Newman as abject farce. No side of politics has a monopoly on honesty or integrity or good behaviour. No side of politics is exempt from misbehaviour. I doubt there isn’t someone in this room that doesn’t have some bias against a political party of one type or another, it could be the Greens, Katter's Australian Party, Palmer’s dis-United Party or Pauline Hanson. I shouldn’t describe that as a bias, if you support Pauline Hanson or Mr Palmer that’s more a symptom of advanced mental disability. But we all have political preferences, and we all tend to think that the party we support are the good guys. If that’s what you think, you have to remember that sooner or later the bad guys are going to get in charge and when that happens you want checks and balances in place.

The reality is different, there are no good guys or bad guys. We have an electoral system, a democratic system, that fortuitously creates good results on many occasions, but is also capable of producing really outrageous results, as we’ve seen over the past century or so. There is one way and only one way that has been proven to prevent that in the other Australian states and in most comparable western democracies. I know, as Professor Aroney said, it doesn’t happen in New Zealand, it doesn’t happen in the ACT, NT and most Canadian provinces, but around the world successful governments are always characterized by a lower house which elects the government and an upper house which is removed to the point of providing some review not only of legislation but of some administrative abuse. I quoted from Karl Marx about history being repeated, Edmund Burke made a similar remark, though a less humorous or more measured version. Edmund Burke remarked that ‘People will not look forward to prosperity who never look backward to their ancestors’. Burke’s point is: repeating history’s mistakes is not inevitable, repetition is just the default position, if you do nothing about it, if you don’t learn from what’s gone before, only then will you have problems. We’re in a position to learn from history and we have the ability to bring Queensland up to speed with the most effective system of government that has existed anywhere in the history of the earth.”

[Applause]

The Hon Rachel Nolan

Rachel Nolan: “Thanks Tony, the primary point I’ve taken from that is that Queensland politics remains the only show in town, and I think it has ever been thus. I could on a light note rebut that while many of us in considering this question would make the argument, as Tony does, that there is an innate backwardness or conservatism and frequent corruption, when compared to other states. It can be argued, but I won’t argue it, by want of our different structure we are more backward. I think the Herston example contradicts that in and of itself, in that it took the South Australians who usually pride themselves on their progressiveness until the 1970s to get Don Dunstan, but we had Herbert back in colonial times.

I’m going to begin with a confession of my own, when Rose came to me and asked me to speak on this topic I initially said no. I wanted to help her and so I cast around asking people I know on the progressive side of politics to find an alternative to speaking myself. I spoke to two Cabinet Ministers, two former Cabinet Ministers, three academics and three rising stars of the Labor backbench, and it seems everyone is re-arranging their sock draw tonight. So that’s how you ended up with a tired old has-been like me. There is however something in this, this topic, should we restore an upper house in this state, is something of a boring old chestnut, it has been discussed at length over the years and no doubt it will continue to be discussed for the years to come. I think that those of you who are scholars and those interested in governance think on the face of it that Queensland would simply fit in with the other states, that this is the standard model of democracy and why wouldn’t we have that too? The way it plays out in the political debate, which is where I come from, is that this is a conservative hobby horse. The reason I rang around and couldn’t get anyone to turn up is that progressive people honest to God don’t care. Lawrence Springborg tends to get excited about the issue from time to time, but it’s never been a matter of Labor policy to reintroduce the upper house, despite the modern tendency for progressive governments to put forth more measures extending the franchise of good governance in and of itself. It’s not that we aren’t interested in good governance, but we’re not interest in good governance through the vehicle of an upper house.

Then the question has to become why? Why is this not the law? Why is this a partisan issue, and why does it divide amongst those lines? There are a number of legitimate answers. Tony’s argument is that Queensland has this cracker of a history, that there’s a long history of authoritarianism to the point of corruption, which is true, but there are a couple of points I’ll make in response to that. Firstly, is that this has not been the case for a significant period of time. The great modern watershed in Queensland political history was the election of the Goss Government in 1989. Whilst it is true that the Newman government was extremely unpopular as we all saw, I felt we were terribly unpopular. When we lost and went from loosing a seat like mine and having only seven seats in parliament, I thought everyone hated us. I went overseas for a year and a half, and when I came back I was astonished at the level people hated them. So there were these two spectacular results, but in a way what the demise of the Newman government proves is that review in this state works perfectly well, the Newman government was out of touch and a bit mad, but the electoral system fixed that in the absence of an upper house.

So what would happen if you introduced an upper house in this state? And why is it that conservatives are more drawn to this idea than those on the progressive side? The philosophical reason is this, it is that progressive people want to get in and govern, we want to make social change. The conservatives are more about moderating things. Of course the Newman government was a bit different, but the conservatives who are about moderation, who aren’t about a fire in the belly for social change are more comfortable if their ability to govern is held aside and is moderated by others. But what do we actually get from upper houses? Do we really get a greater system of review or do we simply shift power from the lower house, where we understand how everyone is elected and on what terms and why, to another group of people entirely, to another group of people who are far less accountable and far less well understood than those who we are seeking to moderate?

Lets have a look at it. From my memory from 1994 to 1999, Brian Harradine, a Tasmanian senator, was in power. You can get elected as one of the twelve senators for Tasmania’s half a million people on a small vote, Harradine’s career was marked by this life-long opposition to women’s rights. He held the balance of power for five years. Then you have the Democrats who are at least a political party, and they controversially gave us the GST, then the Greens who used their influence to turn down the possibility of an emissions trading scheme and now you have a ragtag bunch of formerly Palmer independents, you have Jacqui Lambie, one of the people holding the balance of power in the senate, you have Ricky Muir, an illiterate saw-miller from Victoria who was elected with 0.51 percent of the primary vote and Glenn Lazarus known as the brick with eyes. So when you get an upper house, you moderate but you also shift power to a group of people who are not elected on a particular platform who are often elected in crazy and unusual circumstances, who people have never heard of until they find themselves in positions of enormous importance, and then we all act surprise when they do mad things. In New South Wales right now the balance of power is held by a combination of the Shooters and Fishers Party and the Christian Democrat mad-homophobe Fred Nile. In stark contrast, in Victoria power is held by the Shooters and Fishers Party and a party no one had ever heard of ‘Vote One Jobs’ and by the Australian Sex Party.

So what you do with an upper house, you don’t get deep consideration, what you frequently do with an upper house is transfer power to a group of crazy fringe dwellers of whom you have never heard. If the argument is that Queensland has a cracker of a history and the implication is that we would be a little more sophisticated and a little more like everyone else if we adopted everybody else’s system of government. Let’s think in practical political terms of who we would put into those last places, the balance of power places in a Queensland upper house. Who have been the big minor parties to come out of Queensland in recent years? There was One Nation, do you want them in charge? The Katter United Party and most recently Clive Palmer and his cohort. What you would do in practice is to move away from Labor governments or indeed the Campbell Newmans of the world being in a position of power to actually make change, but you would put power directly into the hands of a mad group of rag tag rednecks, gun toting lunatics, the kind of people we have never before seen. This would not by osmosis make us that little more slick, it may well in practice make things much, much worse.

I agree with the essential point that Queensland would be better governed if there was a better level of review. Having eleven years in the Queensland Parliament I think that’s quite certainly the case. At the end of the Bligh years a program of parliamentary reform was developed to deal with this problem, this program had a number of elements, the extension of right to information legislation which was freedom of information on steroids and the bigger change was to the state’s committee system so that the parliament was managed for the first time by a bipartisan committee, there were committees in more direct portfolio areas and the estimates committees were changed so public servants could be questioned directly by the committee. Which is important because unlike political leaders those people just always tell the truth, in committees they just start blabbing it’s awful. So there was an effort to create some review.

There are some limitations to not having an upper house, I don’t dispute that, but one of the first things the Newman government did was to take those things away. One of the most scandalous things they did was to move the estimates committees that had previously run day by day, one committee at a time over a period of two weeks and changed it to where they all happened over a period of one or two days. That along with the changes to right to information takes away the public's ability to scrutinize what’s going on. It is true in an upper house that the people have to be reasonably switched on. They have to pay some attention, and that’s why things like freedom of information and committees can work very well.

There is another reason, which is a more controversial reason but I believe it to be true and that is why it is the conservatives that are always drawn to this issue, and it’s this, there is among conservative politicians in particular in Australia, a kind of hidden but occasionally emerging desire to doth their caps and rub their shoulders with royalty. They love a bit of that sort of thing. It’s why we have Tony Abbott who was formerly the leader of Australians for Constitutional Monarchy. Along with it goes a tendency to believe you can have a bit too much democracy. It might be okay that if for instance as we have in the House of Lords, who aren’t elected at all, if we had more of our own people running the show. You might think I’m just being mean, but how do you think we have had the reintroduction of knights and dames in this country. How is it do you think that the first Australian knight was Prince Phillip? What do you think motivates someone like Bronwyn Bishop to fly around on the public purse, treating everyone like she’s some poor-man’s brand of royalty? What is this sense of entitlement, this sense that the proper people should run the show? It’s not a big streak and it’s not among all of them, but there is a sense that we should have an upper house so that things are done properly in the old-fashioned British way. In examples like those and in the yearning to have an upper house, despite the fact you cannot substantiate the argument that it would give us a better system of governance, you see little twinkles of it, as if they came from the wand of the Queen herself. Never ignore that there is that tiny little streak that underlies what we hear in this debate. You won’t hear it always but you will hear echoes of it from time to time. Thank you.”

Prof. Nicholas Aroney: “Thank you speakers for so eloquently making your cases. I think we need to give you the opportunity to have some questions from the audience, so please are there any questions?”

Audience Member 1: “My question is for Mr Morris QC, you spoke very eloquently on how in Queensland we have had this history of government overreach and you say this will be remedied by an upper house, but is that the case when you look at the Obeid scandal in NSW and other places where there have been gerrymanders in the past? Where you have an upper house there still is often a problem when you have governments being elected with sufficiently large majorities like the Beattie government or Newman where they would have gained control of the upper house anyway. With that in mind, with this problem extending across the states not just Queensland would it actually make a difference?”

Tony Morris QC: “I don’t think an upper house is a panacea for all problems, it wouldn’t deal with Obeid style problems and one can make a catalogue of the topics it can’t answer. What it can answer is exactly the type of problem Rachel spoke about, where you have a well-intentioned and honourable government, like that of which she was a member, that promotes new reforms and then when a new government gets elected those reforms get swept away. An upper house will address the problem of whoever is Premier of the day has absolute power. At least in New South Wales you have ICAC which brought to light the Obeid scandal. The Newman government did its very best to dismantle the system of non-partisan corruption investigations under what was then the Crime and Misconduct Commission. That’s the result of having absolute power in the hands of the Premier. I’ll confess my natural tendency is towards the conservative side of politics, but I think the best Premier of Queensland in living memory was Peter Beattie and because he had the honest and honorable intention of achieving good government the fact he had absolute power to control parliament didn’t matter. It does matter when the electoral system produces an anomaly.

That leads me onto two points I wanted to mention briefly. The first is the architecture of any new system is very important otherwise you end up with the Ricky Muirs and the Brian Harradines and the Pauline Hansons, but those are the results of the distortion in the senate electoral system where half a million people in Tasmania get as many senators as the 5 or 6 million people in NSW. That’s an absurd distortion and wouldn’t exist in a Queensland upper house. The other element is the larger the amount you vote in, in a senate style election, the more chance there is for producing some crackpots. If the number is confined to around five per district, then you will inevitably get two from one side of politics, two from the other and one who is either Labor or LNP or possibly an independent. If there are five you’ll need at least eighteen percent of the vote to be elected, so it’s going to have to be someone reasonably respectable, for example the man whom the Palaszczuk government relies on for his support, Mr Katter Junior. Someone reasonably respectable like that. It’s all about the architecture of the system, it’s not a universal that you’re going to have crackpots ruling the roost, that’s simply not the case.

My final point in response to the question is that the type of upper house that exists in the senate is quite unique and it has distortions in regards to our history, but the upper houses in other states actually do a good job of review. Yes it may be the case that sometimes the balance of power is held by fruit loops but we tend to attach too much significance to the balance of power because if the major parties agree on something, then the balance of power doesn’t enter into it. The balance of power only arises when the parties are at odds. It may sound odd, but I’d prefer to have an illiterate saw-miller from Victoria than a system where one person has absolute power, and that’s the system we have at the moment.”

Audience Member 2: “This is for Ms Nolan, you spoke of progressive governments wanting to act in a progressive manner. A progressive government is currently in power and they’ve spent a lot of time repealing the decisions of the previous government. If we had an upper house, even if it was filled with crazies, they would only have the power to stop legislation. If an upper house existed wouldn’t they have stopped some of the decisions of the previous government, which would have allowed this government to act in a more progressive manner, rather than spending its time correcting the mistakes of the previous government.”

Rachel Nolan: “There’s a huge bunch of issues in this, about how they’re elected and what their powers are, that become matters of design. As a general principle, one reason why we don’t get into the debate, is that whilst it sounds like a good idea on the face of it, an almighty brawl would emerge over its design. So I don’t think you can assume an upper house wouldn’t have the power to introduce its own legislation. To come then to your question of ‘doesn’t a progressive government still get to be progressive?’, the very fact of an upper house not being able to introduce legislation only being able to stop it is kind of unrelated to that point. Nicholas might know more about this than me, but to my recollection when Queensland finally got rid of an upper house in 1922 there were many issues, but the most significant issue that the Ryan Labor government had been trying to get up was the introduction of a workers compensation scheme. Those who were appointed in the upper house were the landed gentry and were opposed to the workers compensation scheme for their shearers who cut themselves all the time, but you can still block whatever you like, and that is an impediment to the progressiveness of a progressive government.

What played out in the Whitlam years, was that the Liberal upper house was opposed to a number of reforms that the Labor government was seeking to make. One of those scandals was the Khemlani loan scandal, where money was borrowed from a shady middle-eastern oil baron, which later became a mainstream thing to do, but that government was stymied from implementing its agenda, by the more conservative upper house which didn’t want to see Australia going down, what was also ultimately thought by the Australian people to be a radically progressive path. The ultimate answer is that if you can block legislation, you can block the progressiveness of a government and that matters to more leftist governments. This is changing and the Palaszczuk government thus far is the best example of the change. We think we’re here for a good time not a long time, as there have historically been longer periods of conservative rule, so we historically think that our role is getting in and getting into it and that’s why we care about potentially being stymied more.”

Audience Member 3: “This question is directed to Rachel. You made the argument that proper people should govern, but the argument could be made from the other side. Political parties who have a very tight grip on the lower house, MPs who criticize their parties are unlikely to be re-elected for parliament. The parties in the lower house are tightly controlled by parties such as the Labor party, as opposed to a better system that could be introduced in the upper house, whether that be proportional representation or for instance one model is that local council mayors could form an upper house. Now I don’t know if that would be representative, but it would provide a greater range of people and I think it would be unfair to classify all council mayors as crazies.”

Audience Member 4: “Don’t you think part of the problem with accountability, is that accountability is left to the elected members. Take for example the problem with the expenses scandal, such as Tony Burke’s family trip to Uluru. If you take Mr Morris’s point of learning from history, hasn’t it been that in Queensland’s history it has been non-elected committees and commissions that have changed things. One of Fitzgerald’s greatest complaints against the Goss government was its dismantling of the EARC. Some of the greatest reforms have been the introduction of the productivity commission and the strengthening of the right to information. So to learn from history we need to look beyond the traditional Westminster system, one of the best mechanisms of accountability actually came from Sweden through the introduction of Ombudsmen. So do we need to look past the Westminster system for different types of measures?”

Rachel Nolan: “Regarding the first question, I think it’s important not to misunderstand what’s political and what’s structural. That is in so much as it’s true now, it’s a generational thing were young people take this view that politics is done by someone else. When I was at university we thought those sort of people were us and that was probably the case for Tony as well. There is a perception and a reality that party discipline is strong, meaning that political power is locked up in the hands of someone who isn’t us but them. I essential disagree with that view, I believe political power is available to every single citizen. If people become involved, that’s what changes politics. If you want to change politics it’s not in my hands it’s in yours. It’s different from there being an upper house because that’s not a method of political practice, that’s a method of changing the rules and that is indeed something that people in political power at that time can do.

The other thing that I neglected to touch on, that we in the political parities believe we are the right sort of people. There is an extent to which that is true and we who were members of the lower house think that we’re the right sort of people compared to those elected on proportional representation. Keating famously called the senate unrepresentative swill, and it’s abusive but it’s funny and there’s an element of substance to it. The idea that those who are members of the lower house are indeed the right type of people is not based on party affiliation. There is a direct connection between a member for parliament who represents a constituency and those they elect. So when I was the member for Ipswich, I walked amongst those I represented everyday. Senators who represent 0.5 percent of five million people don’t have the direct connection with the constituents they represent and don’t have a direct accountability to those people, and don’t have a relationship with those people in the same way. I recently talked to a person who was in the senate but now serves in the lower house and he or she said to me ‘they just come in and want to talk to you’. Senators have no idea what it’s like to have a connection with the people they represent because it’s so many people who are often so far away.

When you have a direct relationship of representing the electorate, you develop a deep relationship and responsiveness to what those people want and need. So when I take about proper people it’s not about party affiliation, it’s about real, alive and direct accountability. So onto the final point of ‘can we have ombudsman, a supreme court and all these other bodies of power’. So you’re an anti-democrat. Certainly we should have people of expertise, but we as a citizenry get the politicians we deserve and we do have a responsibility to hold them to account, you can’t just know better. The people I loathe the most are opinionated but don’t vote. We have an obligation, it is a two way street, if people are disengaged then what do you expect? Democracy is participative. There has to be an ultimate accountability. No one else is as accountable to the people as elected members of parliament are.”

Tony Morris QC: “I first want to address what was said about how we get the politicians we deserve. I disagree fundamentally, no one deserves to have Bronnie Bishop as their local member. That might be an extreme example, but the fact is that every political party has at one time produced inappropriate members of parliament. There are a couple who have appeared in the newspapers in the last few months from the Palaszczuk government, but no political party has so far been able to find a way to prevent some people from slipping through the cracks.

The only way to prevent those people achieving absolute power as exercised by Ned Hanlon, Joh Bjelke-Petersen and Campbell Newman is to have an upper house, there is no other way. If I was doing this as part of my day job, and being a little more ruthless than is appropriate, I would say the argument against me is bizarre. It amounts to two propositions, one is that if you have an upper house you’re going to get a lot of fruit loops and the other problem is that the people who want an upper house want it because the right sort of people will occupy it. As I say it’s all about architectural structure. I have a controversial view of my own that if we have an upper house, the members should have a lengthy term of six or eight years, but they should then be ineligible to stand again for either house of parliament for as long as they have been a member of the upper house, as a way to ensure that people going into that house don’t do so as a long term career expectation that they will spend the rest of their lives occupying a seat in parliament, but on the basis that they can do what their conscious tells them to do, not what the party dictates, not necessarily even what the community dictates but what they in their heart of hearts believe they should do, with neither an expectation of being rewarded should they decide to follow the party line, nor an expectation to be punished if they go in the opposite direction. This is probably an extreme view, but I mention it in regards to the fact that it all depends on the structure.

Certainly the notion that an upper house is going to attract odd bods is completely answered by saying it’s completely dependent on how you design it and if you have optional representation with three or five members for each district this problem just doesn’t arise. I’m particularly interested in the second question, which I think is a particularly insightful one. It is true undoubtedly that some of the best work in terms of good governance, comes from people who aren’t politically elected. Judges, royal commissioners and commissioners of inquiry, organisations such as ICAC, ombudsmen and specialist ombudsman such as the telecommunications ombudsmen and the banking ombudsmen, but also public servants who are apolitical and just do a good job regardless of who is in power. They do great work, but for those organisations to be able to achieve that protections need to be in place.

Take for example a right to information commissioner who is ensuring that the public get the information they need to see if anything is going wrong in government, you need to have the legislation in place as it was brought in by the Bligh government but you need the protection that the next government to come into power can’t undo it all, which is precisely what happened with the Newman government. We had world-class legislation brought in by the Bligh government, but what use is it to anyone when the next government can dismantle it. So yes, the non-political branches of government are hugely important but that has to be on the basis of an administrative and legislative structure that is responsive to community requirements and can’t be undone at the whim of one person.”

Rose: “Unfortunately this marks the end of tonight’s lively debate. Thank you very much to our panel, Professor Nicholas Aroney, Mr Anthony Morris QC and Ms Rachel Nolan. I thoroughly enjoyed tonight’s debate, I’m a little more confused but I’m positive everyone in the audience is as well. Could everyone join me once more in saying thank you to our speakers.”

[Applause]